A Slow Farewell to Gaetano Pesce

)

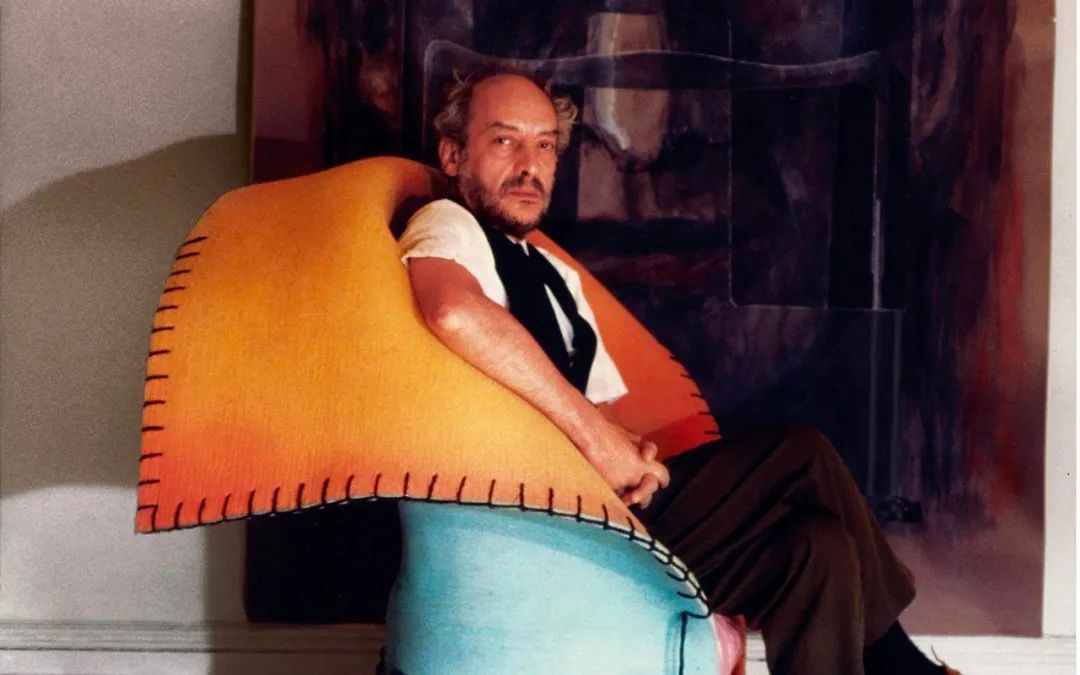

The interview with Gaetano Pesce for the exhibition "Nobody's Perfect" was conducted three years ago. At over 80 years old, he appeared spirited, exuding the uplifting Italian warmth and passion that still left a lasting impression. Midway through the interview, he looked at our group of young people and said, "I am old now, and you are young. If there's one thing I must say, it is 'cherish your time.'" At the time, we pondered his words, but little did we anticipate that the time to bid farewell would come sooner than we imagined.

In early April this year, Gaetano Pesce passed away at his home in Manhattan. Spending half a century crafting furniture, architecture, and venturing into various fields including kinetic art, film, interior design, and urban planning, Pesce's legacy and imprint are so intense that they scarcely need further introduction. His designs will not fade away; instead, they will continue to exist in a more vibrant form.

My Design is about Joy

Born on November 8, 1939, Gaetano Pesce hailed from La Spezia, not far from Genoa in northern Italy. His father served in the Italian Navy and passed away during World War II, leaving Pesce's mother to raise him and his two siblings with the help of their extended family in northern Italy. The culture in Italy was like a thunderstorm, and it wasn't until later that Pesce realized the impact of the place on him: "It was those conversations about music and art that helped us survive."

From 1958 to 1963, Pesce studied architecture at the University of Venice under the guidance of architect Carlo Scarpa. He co-founded the avant-garde art group Gruppo N with eight other architecture students, stating, "I wasn't satisfied with what I learned because I didn't find it interesting. I was curious about materials."

Shortly after graduating from the University of Venice, Gaetano Pesce's keenness for the avant-garde was already apparent. He reached out to several local chemical companies, hoping they would tell him how to handle their products. His bold requests were not rejected; on the contrary, two companies invited Pesce for visits. Reflecting on this later, he said, "I realized that no one in my era taught me about materials," and he saw "incredible things."

From there, resin, fabrics, polyurethane... these became Pesce's signature materials. Despite being from Venice, he believed resin was superior to glass because "you work with it today; tomorrow, it's ready." This viscous material from the Middle Ages, durable, translucent, and easy to use, with its softness, resilience, and malleability, helped Pesce break free from the constraints of clean, rectilinear modern design. "The overwhelming design consensus, the traditional material hierarchy, or the authoritarian order of architectural modernity" collapsed here, as the material directly shaped Pesce's flexible, concrete, and captivating worldview.

Before being engulfed in the whirlwind of radical design experiments in the 1960s, he had studied architecture in Venice. While many of his contemporaries lost momentum or decided to cater to bourgeois tastes, Pesce never stopped trying new materials, shapes, and prophecies. —Curb Magazine

Pesce once held an exhibition at the Aspen Art Museum and completely transformed its horizontal and vertical appearance, which was the primary condition for hosting the exhibition here. During the interview at the exhibition, he mentioned, "My visual language is to create joy, which is always a response to what is happening in the world. If there's a war, I have to do something, and if possible, I hope to make people laugh or smile.

In this way, this work plays an important role: if you're not just adding material to an object but adding material to a viewpoint, whether it's political, social, or religious, then it becomes art."

Escaping from catastrophic repetition, design is his political manifesto

If there's one word that will never appear in Gaetano Pesce's life manual, it must be "order."

In 2019, Pesce mentioned in a speech at Columbia University: "Repetition in life is a disaster. Order belongs to totalitarianism." Pesce thought about color, shape, texture, material, and storytelling from a political science perspective, which is why all political expressions have always existed in his designs in a clear and bold manner.

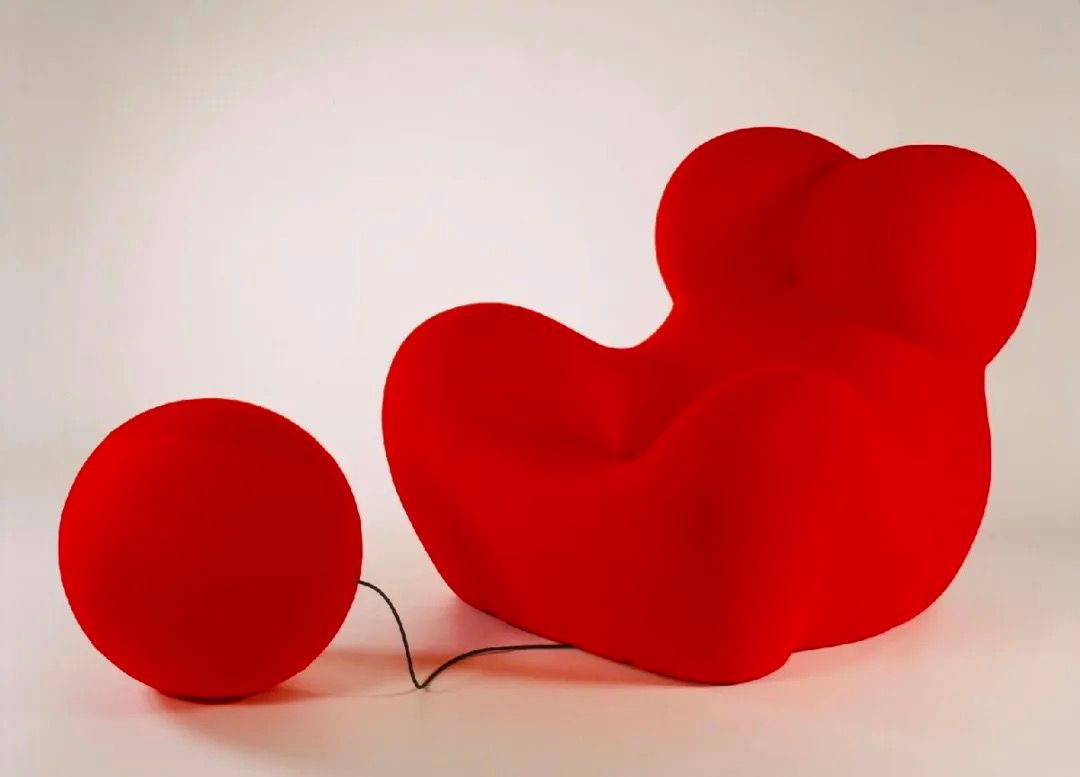

However, this undoubtedly put Pesce on the edge—The Up5 Chair is Pesce's most famous and controversial work. At the time, he was studying how to make a chair with polyurethane, and the Up5 Chair was born from this. But Gaetano Pesce was not satisfied with breaking through on materials alone; he imbued this work with another layer of meaning through its form. Due to its curved edges and structure resembling a ball and chain, the Up5 Chair came to represent gender inequality.

"It's an image of a prisoner, a woman suffering from men's prejudices. This chair should have discussed this issue." In his view, unlike other modes of communication, a chair can bring political statements directly into the home.

"Up 5" Chair © Gaetano Pesce

And the choice of flexible, reshaping material also stems from a response to the nature of the times: "For me, beauty means uniqueness, being different—I like beauty full of mistakes because we are all human. Perfection belongs to machines, it is outdated and no longer exists."

Just as he emphasized later to The New York Times:

For me, international style architecture reflects the same political ideology; we must think or dress the same way. I believe the wealth of the world is diversity. Only one ideology is a disaster. If we are the same, we cannot speak because there is nothing to say. But if you and I are different, there are many things we can exchange.—Gaetano Pesce

I don't exist in New York

Since 1983, Gaetano Pesce moved from Italy to New York and lived and worked here until his passing. In the early 21st century, Gaetano Pesce moved his studio from SoHo to the Brooklyn Navy Yard to make room for up to eight full-time assistants. In 2016, he joined the renowned gallery Salon 94 located in the Upper East Side of Manhattan. The skyline of New York later became the inspiration for his creations, yet his relationship with this city was always like that of a passerby, maintaining a distant connection.

"Even now, I don't exist in New York," Pesce said thoughtfully in an interview. "Many people think I live in Italy, but here, I don't exist." Pesce lived in the Upper East Side, preserving his showroom near Broadway and Prince, commuting to the studio near the Brooklyn Navy Yard when he needed to work hands-on—"This is my New York triangle," he said with a smile.

Pesce's identity was integrated with his creations, with little semblance of being a "New Yorker," and even spoke Italian most of the time while in New York. Gaetano Pesce's inherent Italian style in his creations was what garnered attention in this city: "This style of expression, sometimes romantic, sometimes bizarre, seems unlikely to come from a city submerged by cynics and modernists." In his own words, "I come from Venice, where the culture is full of light and color, while New York is declining, it's deteriorating."

Nevertheless, in the last few years of his life, Pesce still gave New York a romantic gift—Danilo Scarpati.

This resin-made triptych screen was an accessory to his sofa Tramonto made in New York in 1980, reflecting the skyscrapers of Manhattan, with the fiery sun rising on the skyline. This true metropolis, with so many problems, is full of chaotic, contradictory charm, captivating the gaze for a long time.

Like many of Pesce's works, this piece still contains fierce expressions behind it: he was concerned that this city had lost its inspiring power because it had been disrupted by economic decline and crime. And the theme of the skyline was Pesce's hopeful note, reminding us that suffering is often short-lived. "I believe the screen not only has practicality but also expresses a positive and optimistic view of a better world in the future."

Critic and curator Glenn Adamson once described Gaetano Pesce as follows: "He has no rationalism but provides wild destructive energy and provocation." As he aged, Mr. Pesce seemed to become more productive.

That's absolutely right—starting from entering the creative industry, Pesce never stopped working, even during the pandemic, and as time passed, his works burst with even stronger vitality.

The Pratt-style Chairs launched in 1984 are a series of resin chairs. That year, he began an internship at Pratt Institute in New York, where he used Pratt's studios and materials to realize his vision for a series of resin chairs.

Around 2020, Gaetano Pesce designed 400 colorful resin floors and resin chairs for the Bottega Veneta Spring/Summer 2023 fashion show in Milan. This show was not only a great success but also made the fashion world aware of the name "Gaetano Pesce."

In the early 1990s, Gaetano had many bold architectural ideas, although they never came to fruition, they continued to inspire modern society. In 2016, British artist Anthea Hamilton was shortlisted for the Turner Prize, and her work included a "Door Project" (Project for Door, After Gaetano Pesce) consisting of a door made up of a pair of oversized decorative human buttocks, replicating an unrealized Pesce design.

Gaetano Pesce is destined to be a name that cannot be easily forgotten. Especially when reinterpreting him in the third decade of the 21st century, he places his future importance in context. That's why we still hope to rewrite his story, as there are surely undiscovered humor, provocation, and endless creativity in those winding paths.